Why the unlawful use of personal data matters

Data, and its misuse, has become commonplace in the media headlines recently. Anne Wesemann, Lecturer in Law at The Open University Law School takes a look at one recent data privacy storm, and explains the implications on democracy of the unlawful use of personal data.

A complex data storm

The Cambridge Analytica whistleblowing storm is about democracy and how real democratic processes need to operate within the rule of law. It is NOT about the result of the UK’s referendum regarding EU membership and it cannot automatically undo the result and the steps the UK has taken and continues to take in leaving the European Union.

After all, it is the UK government and UK parliament that are progressing the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. The referendum itself had no immediate legal impact.

At the heart of the storm are three men, the latter two in the recent limelight: Darren Grimes, Shahmir Sanni and Christopher Wylie.

Wylie sat before the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Commons Select Committee on Tuesday, 27th March 2018. Watching him respond to MP questions shows the complexity of what he and others are aiming to unravel. To put it simply: one accusation is that the Leave campaign cheated by overspending. A second accusation relates to how information about potential voters was sourced, analysed or even misused.

Strict rules on sharing personal data

Wherever and whenever you share information about yourself, you will be asked to confirm you are happy for that information to be used, stored or otherwise shared.

Facebook allows you to download your data and see what information the company holds about you or even others. There are strict rules regarding the way your personal information can be handled and shared and these are currently set out in the Data Protection Act. While the law will change in May 2018 to give room for an EU regulation, the current law is what will be applied to any investigation into the whistleblower allegations.

Data used to drive political campaigns

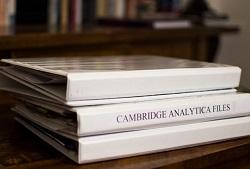

During the committee hearing, Wylie explained how a net of companies was founded solely for the purpose of harvesting personal information and analysing it to support the political campaigns of a variety of clients, the Vote Leave Campaign in the UK EU referendum being one.

They were responsible for the provision and analysis of diverse datasets enabling those provided with that information to launch very narrowly focused and effective campaigns. This net of companies is a challenge to unravel but at the heart of it stands Cambridge Analytica.

Why cheesecake matters

Whenever personal data protection is discussed, we see comments along the lines of: “Well, if they want to know where and when I eat my favourite cheesecake, so be it. Why does that matter?”

It matters, because you should be asked what happens with information about you. We might not always know the value of our simple information which is why we need to be protected when we are sharing it. If only to be made aware that information about us is in the open.

What if it isn’t cheesecake, but your daughter’s school? Your son’s whereabouts over the last few months? You or your partners spending over the past year? Information about ourselves belongs to us and the moment we share it we lose control over how it is spread, saved and put into context with other information.

This is why transparency is key.

Democratic votes have rules

The UK’s referendum on EU membership was pitched as a truly democratic exercise. The UK government continues to emphasise that “the people have spoken”.

In order for a vote to be a truly meaningful democratic exercise, those taking part in it must play by the rules. These rules relate how potential voters can be contacted, how campaigns can be run, but importantly they are very strict when it comes to the amount of money that can be spent on the campaign.

In the example of the referendum, any campaign that was not registered with the Electoral Commission was only allowed to spend £10,000 on its campaign. Once registered, a campaigner is able to spend up to £7million, including any spending on sub-groups. This is where Wylies’ and Sanni’s statements and shared information are coming into play. Wylie was working for Cambridge Analytica, while Sanni worked for an independent referendum campaign organisation BeLeave, focussing on the youth vote.

The Vote Leave and BeLeave link

In its application to the Electoral Commission to become the campaigner for leave, in order to secure the £7million allowance, Vote Leave listed BeLeave as a “community-related, minority and specialist interest group”.

But we now know that both campaign groups worked in close proximity to one another, sharing an office building, staff, funding and with BeLeave working under direct influence of Vote Leave. Relying on communications publicised by Wylie and Sanni, the Leave campaign directly influenced the communications of BeLeave and oversaw their budget and spending.

This in itself is not illegal at all.

BeLeave would simply be part of the Vote Leave campaign group, officially recognised by the Electoral Commission. The whole group would be able to split the £7million between them as they wished in their coordinated campaigning.

Vote Leave did not do that though.

A series of other campaign groups are officially listed as part of the group, but BeLeave is not one of them. Yet it seems that campaigns were agreed between the two groups and money moved from an external source to BeLeave to then be spent in the bigger campaign.

Why campaign group spending is a democratic issue

Again, some may say, so what? Why is the spending of campaign groups a democratic issue? Let’s go back to the cheesecake example.

A new shop opens across the road from your favourite cheesecake place. You can smell the delicious bakery products in the street. It is a small shop, they don’t run any advertising as they cannot afford it, but they keep their windows open so the smell speaks for them.

Your favourite cheesecake is sold by a corporate brand. A couple of days after the store across the street opens, they start a campaign including discount vouchers through letter boxes, free cake samples at every corner and a cheesecake happy hour every other week. The new store eventually closes down.

Election needs to ensure people campaign equally

An election, as any public vote, needs to ensure an equality of spending in order to allow information through campaigns to be spread not evenly but to equal amounts. We need to trust that campaigners play by the rules so that our personal views are not manipulated through excessive campaign spending. If we are allowing uneven spending, or very aggressive forms of campaigning including the sharing of wrong information, our beliefs are not built on facts, but on what others want us to believe.

This is what undermines any democracy.

If we believe there is only one cheesecake, we’ll never follow that wonderful bakery smell.

Anne Wesemann, is a Lecturer in Law at The Open University Law School. This article was originally published on The OU News website. Click to read the original article.