The Snail that Never Was? 90 years on

By Gillian Mawdsley, Associate Lecturer, The Open University Law School

Take a small creature with a shell that moves slowly and eats garden plants, add a Scottish term for a fizzy soft drink and a large town in the West of Scotland. And what do you have?

From any first year law student to an elderly lawyer, the eyes will glaze over wistfully. They will say snail, ginger beer and Paisley, then, Donoghue v Stevenson and if you are lucky, the case citation of 1932 AC 562 and/or the name Lord Atkin will follow.

However, how many now recall that on 26 May 2022, it is the 90th anniversary of the judgment issued from Lord Atkin. That judgement went on to become a global phenomenon, recognizable today to generations of law students. In simple terms, this seminal five-judge decision, emanating from the House of Lords, set out the foundation for the law of negligence in common law jurisdictions across the world. It established the principles of the duty of care and the neighbour principle. It is the foundation case in tort in England and Wales and delict in Scotland.

But then we may ask, was there actually a snail? We need to go back to the origins of the case where the facts are familiar to many.

At 8.50pm on 26th August 1928, May Donoghue went from her home in Kent Street, Glasgow to meet a friend at the Wellmeadow Café, Paisley, whose proprietor was Thomas Minchella. Her friend, about whom certain speculation abounds (as Mrs Donoghue was a married but separated lady at the time) bought her an ice cream and a “ginger beer” to form an ice cream float. The ginger beer was then produced in an opaque brown-coloured glass bottle by the manufacturer, “D Stevenson, Glen Lane, Paisley.”

After Mrs. Donoghue had drunk some of her drink, her friend went to refill her glass. At this time, it was alleged that she saw what she believed to be the partly decomposed remains of a deceased snail. Some three days later, Mrs Donoghue sought medical treatment for shock and gastroenteritis and a further three weeks later, further treatment at Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

May Donoghue then sought to sue the manufacturers, D. Stevenson, claiming £500 in respect of her injury. The action was raised by a Glasgow solicitor and city councillor, Mr. Walter Leechman. He had, crucially, been the solicitor in two earlier unsuccessful actions raised against the well-known Scottish Irn Bru manufacturer, A.G. Barr & Sons, where there had allegedly been mice in their drinks.

Mrs Donoghue was successful at first instance at the Court of Session with the Lord Ordinary. She then lost on appeal where the Court of Session upheld that Stevenson as the manufacturer owed no duty of care to an ultimate consumer unless the consumer had a contract with the manufacturer requiring such care. Mrs Donoghue had of course no such contract as indeed her friend had bought the drink. Had her friend sued, there would have been no dispute.

Mrs Donoghue then appealed to the House of Lords. In order to take her case to the House of Lords, as she had no money and would have required to provide security for the costs, she had to declare herself a pauper swearing that “I am very poor and am not worth in all the world the sum of five pounds.”

The case was heard on 10 and 11 December 1931 before five judges Lords Buckmaster, Atkin, Tomlin, Thankerton, and Macmillan. The verdict when issued was a majority verdict 3:2 with Lord Atkin, an Australian-born/Welsh judge and the two Scottish judges, Lord Thankerton and Macmillan, upholding her right to claim.

The judgment associated with Lord Atkin, now so famous today, held that a manufacturer of food, is under a legal duty to the ultimate purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care that the article is free from defect likely to cause injury to health. It is commonly understood in the “neighbourhood judgment” stated by Lord Atkin who said:

“You must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be — persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.”

The underlining is my emphasis. His judgment resonates with tones of morality and a nod to the parable of the biblical “Good Samaritan.” And what happened next?

Mrs Donoghue had won her right to sue. The “Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette,” at the time apparently described Mrs Donoghue as Mrs Macalister (her maiden name) reporting the House of Lords decision as “Appeal allowed: Snail in Ginger Beer Case.” The case was remitted back to the Court of Session so that a case could be heard in January 1933. At that case, Mrs Donoghue would now have had to establish the relevant facts, namely the presence of the snail, the negligence of Mr Stevenson and her injury through her illness.

However, in the intervening period, the respondent, David Stevenson, died so his executors settled the claim out of court for what was allegedly £200, worth approximately over £14,000 today.1 However there had been no case. There were no witnesses. There was no evidence.

The significant impact of the decision in the case continues. It was described in July 2010 in “The Snail and the Ginger Beer: The Singular Case of Donoghue v Stevenson” lecture2 as having been “unleashed upon a common law world that was clearly ready for it, [and] the neighbour principle drove the development of the modern law of negligence. Expansions and contractions of the duty of care in negligence and applications of the tort to new factual situations in the decades since 1932 are measured against Donoghue v Stevenson and Lord Atkin’s neighbour principle in particular.”

But was there a snail? No-one knows for certain. It seems to matter little now, given how the law of tort (or delict in Scotland) has developed.

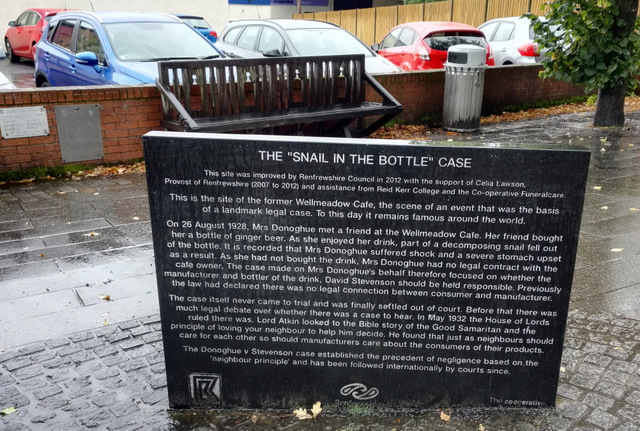

Let us remember Mrs Donoghue and Mr Stephenson’s case that inspired us all as budding law students, English, Scottish and further afield, to recall the case which we encountered in these, our early struggles, in the study of law. Let us too remember too as tangible evidence that there is a small corner in Paisley with a park, bench and memorial stone where that café once stood.

Image: geograph

Let us then raise our glass of ginger beer, metaphorically, to one snail, true or false, on this the judgement’s 90th anniversary.

References

- CPI Inflation Calculator (accessed on 15/5/2022)

- ICLR lecture transcript 2010 (accessed on 15/5/2022)

Gillian Mawdsley

Gillian has been an OU tutor for five years. She is also a practising Scottish solicitor whose professional legal background was mainly public sector experience in the criminal law sphere. Her academic teaching in Scotland spans Edinburgh and Strathclyde Universities where she teaches delict or tort. The “snail” case is the Scottish legal profession’s claim to fame- and is only 10 miles from her home.