Five research questions answered!

Blog post by Fred Motson

When I was asked to give a talk as part of the Belonging Project on something directly relevant to law students, I found it simple enough to decide on the topic – research sources.

I’ve taught at a wide range of institutions on a range of access, undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. Yet everywhere I have taught and whatever group of students I’ve been teaching, I’m always asked: “What is an appropriate research source?”

And then, perhaps more importantly, the follow-up: “how do I find them?”

Why do research sources matter?

A persistent myth is that tutors count up the number of sources in a piece of student work and award a grade based on the quantity. This is absolutely not true! Using sources is crucial to any piece of legal work, whether academic or professional, but the old aphorism of “quality over quantity” always applies.

Imagine a lawyer defending her client who is accused of theft. She calls 50 witnesses who all say they think the defendant is a lovely person who would never steal anything. Is that particularly useful evidence? What about a single CCTV tape showing the defendant was in a completely different part of the city at the time of the theft? In that instance, one piece of evidence has far more weight than fifty. The same applies to research sources.

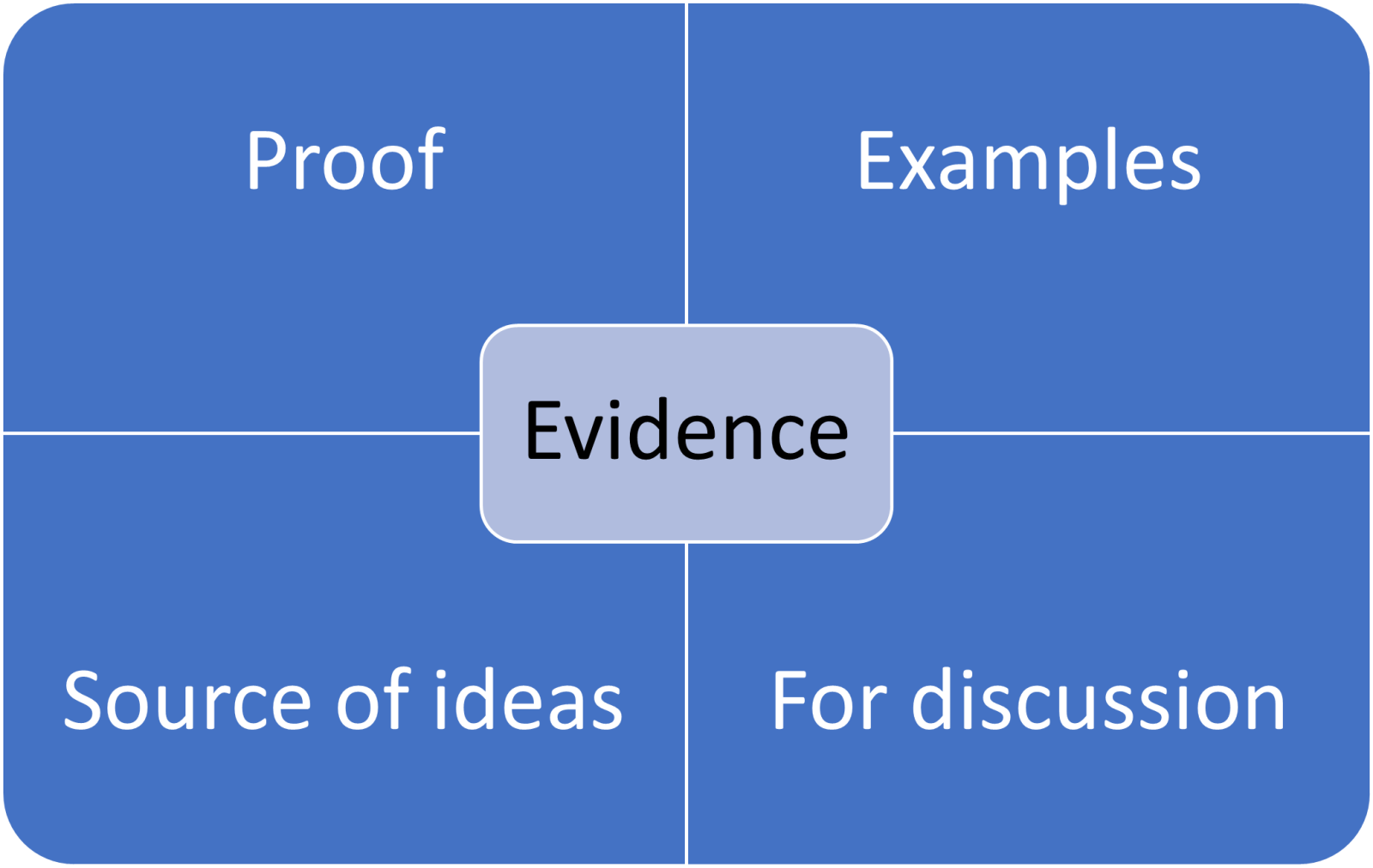

At heart research sources are the same as the CCTV tape – they are evidence for what you are trying to argue. That might be because they prove your point (that’s ideal!) but it might also be because they give an example of something you allege. It might even be that they are sources of ideas you do or don’t personally agree with, but which have given you ground to develop your own arguments upon.

An academic legal essay that doesn’t cite external sources is the same as a lawyer standing up in court and saying “I’ve got no evidence but personally I think my client is a lovely person and deserves to win!”

What is an “appropriate” source?

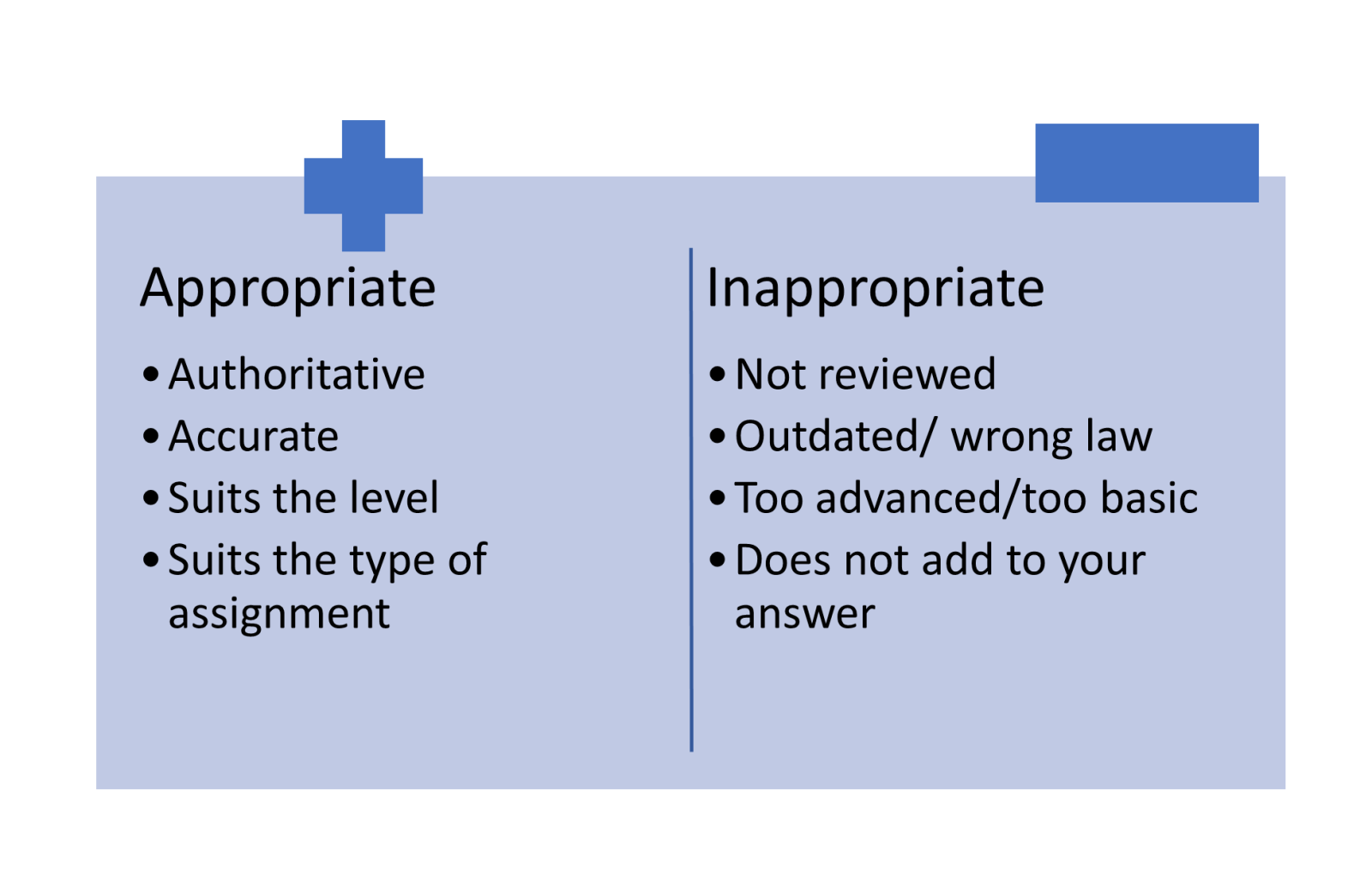

So are all sources born equal? Again, remember “quality over quantity”. Not all sources are equal, but the most important priority is to include appropriate sources and exclude inappropriate sources. The diagram below shows what this might mean.

An appropriate source is authoritative, which means it has authority. Primary legal sources (the law itself, e.g. statutes, case law etc.) obviously have that authority but this also means secondary sources (writing about the law) can be authoritative if they are generally accepted as such. So well known books, articles in peer-reviewed journals, the unit materials you read as part of your study: all of these are checked and rechecked by a wide range of independent academics and practitioners.

What sources should I avoid?

On the other side are, for example, websites which claim to state the law but do not explain who has checked their accuracy. Sometimes searching the web (rather than searching through the Library website or legal databases like Westlaw) finds amazing and authoritative content – but sometimes it returns sources which no one has checked and which could have been written by someone who:

- Doesn’t know the law

- Doesn’t understand the law

- Knows the law but doesn’t know the law has changed

- Knows the law but is talking about a different context/jurisdiction

A really good way of assessing sources is the PROMPT criteria, which you will study further as part of your LLB studies (with particular focus on PROMPT in W211 Public law)

What sources should I use?

What is a relevant source depends on what it is you are being asked to write. If your assignment requires writing advice to a client or a court submission, you are likely to focus mainly if not exclusively on primary law such as case law and statutory provisions. If you are writing a traditional academic essay, you are likely to be using more secondary sources such as books and journal articles. If you are writing on a current, newsworthy topic (for example, legal aid cuts) you might be using a lot more journalistic sources like newspapers and industry websites.

Always think about why you are using the source – are you relying on it to prove a fact, to spark a discussion or to analyse the law?

How do I find appropriate sources?

First and foremost, start simple. Too often students try to find unusual or unique sources, when almost all research starts with the basics. Read the unit materials. Read your textbook or any additional readings given on your module. These will not only help you get a general understanding of the topic but also will give you ideas for where to go next in your research. That might be directly, in following up e.g. sources cited in the footnotes; or indirectly, such as by giving you an idea of keywords you can search for on legal databases or through LibrarySearch.

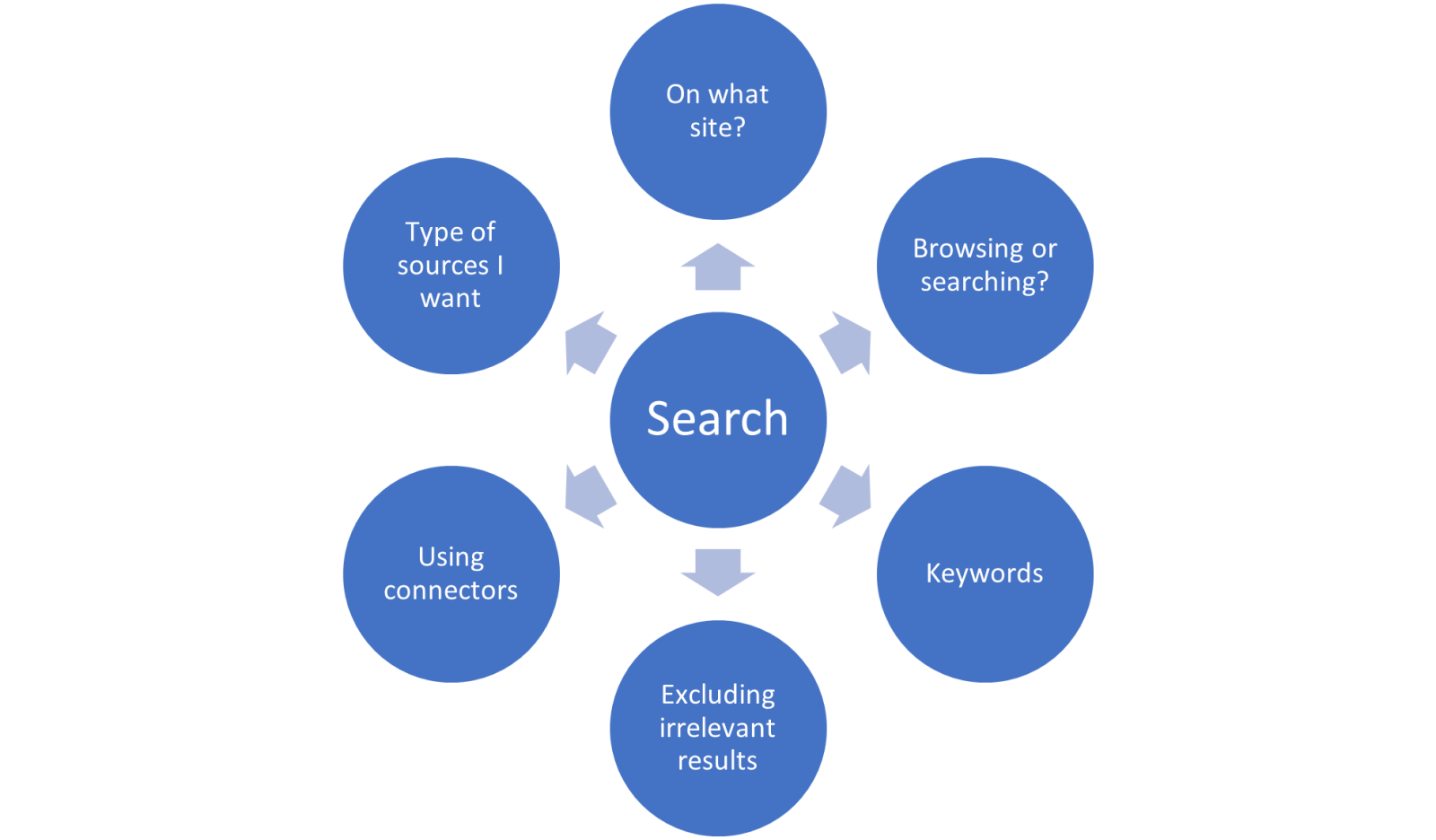

Remember its reSEARCH – search skills are absolutely key, especially in the internet age. The diagram below highlights some of the questions you need to ask before you start searching.

Never ever think typing your assessment question into Google is the place to start!

It might feel like you are wasting time planning research when you could be searching, but much like planning an essay every minute you spend preparing tends to mean many more minutes saved in the actual execution – and a better essay at the end of it.

For more information about research skills, you might want to begin with the following OU resources:

Law Study Home (specific legal research advice)

Library resources (finding sources, sources for your area etc.)

Library training (especially referencing)

Student Hub Live (planning, note taking, critical thinking etc.)

Best of luck with your research journey!

.jpg)

Fred Motson

Fred is a Lecturer in the Law School at the Open University. His career in Higher Education has been predominantly focused on teaching and Fred has taught across more than 20 different areas of law, at levels ranging from foundation level to postgraduate and professional courses.

At present Fred is heavily involved in designing and writing the new LLB Law degree which began to go live in 2021, having written units on W111 Criminal Law, W112 Tort and Civil Justice, W211 Public Law, W212 Contract Law, W311 Trusts Law and W323 SQE: Business Law and Dispute Resolution. Fred is also currently Chair of the 22J presentation of W112. He also teaches Equity, Trusts and Land Law as an associate lecturer.

After more than a decade of full-time teaching, Fred became a student once again in 2021 when he commenced studying for his PhD through the Open University. His research combines two of his main interests, sport and technology, as it is focused on applying legal theories about interpretation and judicial decision-making to the use of the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) in professional football.